Which Method of Creating Art Was Used to Produce Over 6000 Life Sized Ceramic Warriors and Horses?

| UNESCO Earth Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Lintong District, Xi'an, Shaanxi, China |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, three, 4, vi |

| Reference | 441 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Website | www |

| Coordinates | 34°23′06″N 109°16′23″E / 34.385000°N 109.273056°E / 34.385000; 109.273056 Coordinates: 34°23′06″N 109°sixteen′23″E / 34.385000°Due north 109.273056°E / 34.385000; 109.273056 |

| Location of Terra cotta Regular army in People's republic of china | |

| Terracotta Army | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 兵马俑 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 兵馬俑 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Soldier and horse tomb-figurines | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Terracotta Regular army is a collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the beginning Emperor of China. It is a class of funerary art cached with the emperor in 210–209 BCE with the purpose of protecting the emperor in his afterlife.

The figures, dating from approximately the late third century BCE,[1] were discovered in 1974 by local farmers in Lintong Canton, outside Xi'an, Shaanxi, Cathay. The figures vary in height according to their roles, the tallest being the generals. The figures include warriors, chariots and horses. Estimates from 2007 were that the three pits containing the Terracotta Army held more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which remained buried in the pits nearly Qin Shi Huang'due south mausoleum.[ii] Other terracotta non-armed services figures were found in other pits, including officials, acrobats, strongmen, and musicians.[iii]

History

The mound where the tomb is located

The construction of the tomb was described by historian Sima Qian (145–90 BCE) in Records of the Grand Historian, the get-go of China's 24 dynastic histories, which was written a century after the mausoleum'due south completion. Piece of work on the mausoleum began in 246 BCE shortly after Emperor Qin (then aged xiii) ascended the throne, and the project eventually involved 700,000 conscripted workers.[iv] [v] Geographer Li Daoyuan, writing six centuries after the first emperor'south death, recorded in Shui Jing Zhu that Mount Li was a favoured location due to its auspicious geology: "famed for its jade mines, its northern side was rich in gold, and its southern side rich in cute jade; the beginning emperor, covetous of its fine reputation, therefore chose to exist buried at that place".[6] [7] Sima Qian wrote that the first emperor was buried with palaces, towers, officials, valuable artifacts and wondrous objects. According to this account, 100 flowing rivers were simulated using mercury, and above them the ceiling was decorated with heavenly bodies, below which were the features of the land. Some translations of this passage refer to "models" or "imitations"; even so, those words were not used in the original text, which makes no mention of the terracotta army.[4] [eight] High levels of mercury were plant in the soil of the tomb mound, giving acceptance to Sima Qian'southward account.[ix] Later historical accounts suggested that the complex and tomb itself had been looted by Xiang Yu, a contender for the throne afterwards the death of the first emperor.[10] [11] [12] However, there are indications that the tomb itself may not have been plundered.[13]

Discovery

The Terracotta Army was discovered on 29 March 1974 by a group of farmers—Yang Zhifa, his five brothers, and neighbour Wang Puzhi—who were digging a well approximately 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) east of the Qin Emperor's tomb mound at Mountain Li (Lishan),[14] [15] [xvi] [17] a region riddled with cloak-and-dagger springs and watercourses. For centuries, occasional reports mentioned pieces of terracotta figures and fragments of the Qin necropolis – covering tiles, bricks and chunks of masonry.[18] This discovery prompted Chinese archaeologists, including Zhao Kangmin, to investigate,[xix] revealing the largest pottery figurine grouping ever found. A museum complex has since been constructed over the area, the largest pit existence enclosed by a roofed construction.[20]

Necropolis

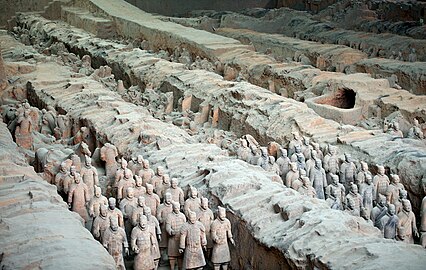

View of the Terra cotta Army

Mausoleum of the Offset Qin Emperor, Hall 1

The Terracotta Army is office of a much larger necropolis. Footing-penetrating radar and cadre sampling have measured the area to be approximately 98 foursquare kilometers (38 square miles).[21]

The necropolis was constructed as a microcosm of the emperor'southward majestic palace or compound,[ commendation needed ] and covers a large area effectually the tomb mound of the first emperor. The earthen tomb mound is located at the foot of Mount Li and built in a pyramidal shape,[22] and is surrounded by 2 solidly built rammed earth walls with gateway entrances. The necropolis consists of several offices, halls, stables, other structures as well equally an imperial park placed around the tomb mound.[ citation needed ]

The warriors stand up guard to the east of the tomb. Up to 5 metres (16 ft) of reddish, sandy soil had accumulated over the site in the 2 millennia following its construction, but archaeologists found evidence of earlier disturbances at the site. During the excavations near the Mount Li burial mound, archaeologists found several graves dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, where diggers had manifestly struck terracotta fragments. These were discarded equally worthless and used forth with soil to backfill the excavations.[23]

Tomb

The tomb appears to be a hermetically sealed space roughly the size of a football pitch (c. 100 × 75 one thousand).[24] [25] The tomb remains unopened, possibly due to concerns over preservation of its artifacts.[24] For case, after the excavation of the Terracotta Army, the painted surface present on some terracotta figures began to fleck and fade.[26] The lacquer covering the paint can curl in 15 seconds one time exposed to 11'an's dry air and can flake off in only iv minutes.[27]

Excavation site

The museum complex containing the excavation sites

Pits

View of Pit 1, the largest excavation pit of the Terracotta Army

Iv main pits approximately vii metres (23 ft) deep have been excavated.[28] [29] These are located approximately 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) east of the burial mound. The soldiers within were laid out every bit if to protect the tomb from the east, where the Qin Emperor's conquered states lay.

Pit i

Pit 1, which is 230 metres (750 ft) long and 62 metres (203 ft) wide,[30] contains the main army of more than 6,000 figures.[31] Pit 1 has 11 corridors, most more than 3 metres (10 ft) wide and paved with small bricks with a wooden ceiling supported by large beams and posts. This blueprint was besides used for the tombs of nobles and would take resembled palace hallways when congenital. The wooden ceilings were covered with reed mats and layers of clay for waterproofing, and then mounded with more soil raising them almost 2 to 3 metres (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft ten in) above the surrounding ground level when completed.[32]

Others

Pit ii has cavalry and infantry units as well as war chariots and is thought to stand for a military baby-sit. Pit 3 is the command post, with high-ranking officers and a war chariot. Pit iv is empty, perhaps left unfinished by its builders.

Some of the figures in Pits 1 and ii show fire damage, while remains of burnt ceiling rafters have also been found.[33] These, together with the missing weapons, have been taken as evidence of the reported annexation by Xiang Yu and the subsequent burning of the site, which is idea to have caused the roof to collapse and crush the army figures beneath. The terracotta figures currently on display have been restored from the fragments.

Other pits that formed the necropolis have also been excavated.[34] These pits prevarication within and outside the walls surrounding the tomb mound. They variously incorporate statuary carriages, terracotta figures of entertainers such as acrobats and strongmen, officials, stone armour suits, burial sites of horses, rare animals and labourers, as well every bit bronze cranes and ducks ready in an hole-and-corner park.[iii]

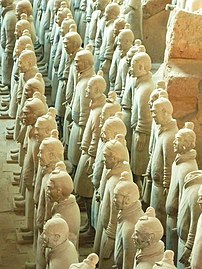

Warrior figures

Types and appearance

The terracotta figures are life-sized, typically ranging from 175 cm (5.74 ft) to near 200 cm (6.6 ft) (the officers are typically taller). They vary in peak, compatible, and hairstyle in accordance with rank. Their faces appear to be different for each private effigy; scholars, nonetheless, have identified 10 basic face shapes.[35] The figures are of these full general types: armored infantry; unarmored infantry; cavalrymen who wearable a pillbox lid; helmeted drivers of chariots with more armor protection; spear-carrying charioteers; kneeling crossbowmen or archers who are armored; standing archers who are not; as well as generals and other lower-ranking officers.[36] There are, however, many variations in the uniforms within the ranks: for example, some may wear shin pads while others non; they may wear either long or short trousers, some of which may be padded; and their body armors vary depending on rank, function, and position in formation.[37] There are also terracotta horses placed among the warrior figures.

Terracotta Army Full general (Left), Mid-rank officer of the Terracotta Ground forces in Xi'an (Right)

Recreated figures of an archer and an officer, showing how they would have looked when painted

Pigments used on the Terracotta warriors

Originally, the figures were painted with: footing precious stones, intensely fired bones (white), pigments of iron oxide (dark scarlet), cinnabar (red), malachite (green), azurite (bluish), charcoal (blackness), cinnabar barium copper silicate mix (Chinese regal or Han purple), tree sap from a nearby source, (more than likely from the Chinese lacquer tree) (dark-brown).[38] Other colors including pink, lilac, red, white,[39] and i unidentified color.[38] The colored lacquer terminate and private facial features would have given the figures a realistic feel, with eyebrows and facial pilus in black and the faces done in pinkish.[40]

Yet, in Eleven'an'southward dry climate, much of the color blanket would flake off in less than four minutes after removing the mud surrounding the army.[38]

Some scholars have speculated a possible Hellenistic link to these sculptures, because of the lack of life-sized and realistic sculptures before the Qin dynasty.[41] [42] They argued that potential Greek influence is specially evident in some terracotta figures such as those of acrobats, combined with rare bronze artifacts made with a lost wax technique known in Hellenic republic and Egypt.[43] [44] All the same, this idea is disputed by scholars who claim that there is "no substantial evidence at all" for contact betwixt ancient Greeks and Chinese builders of the tomb, and the bases of such speculation are often imprecise or simulated interpretation of source materials or far-fetched conjectures.[45] [46] They argue that such speculations residue on flawed and old "Eurocentric" ideas that causeless other civilizations were incapable of sophisticated artistry and thus foreign artistry must exist seen through Western traditions.[45] [46]

Construction

The terracotta army figures were manufactured in workshops by authorities laborers and local craftsmen using local materials. Heads, arms, legs, and torsos were created separately so assembled past luting the pieces together. When completed, the terracotta figures were placed in the pits in precise military formation according to rank and duty.[47]

The faces were created using molds, and at to the lowest degree ten confront molds may have been used.[35] Clay was then added later associates to provide individual facial features to make each figure appear dissimilar.[48] Information technology is believed that the warriors' legs were made in much the same way that terracotta drainage pipes were manufactured at the time. This would classify the process as assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled subsequently being fired, as opposed to crafting a figure as one solid piece and subsequently firing it. In those times of tight imperial control, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on items produced to ensure quality command. This has aided modern historians in verifying which workshops were commandeered to make tiles and other mundane items for the terracotta army.

Weaponry

A bronze helmet unearthed from the site.

An armor unearthed from the site.

Virtually of the figures originally held real weapons, which would take increased their realism. The majority of these weapons were looted soon afterwards the creation of the ground forces or take rotted abroad. Despite this, over 40,000 bronze items of weaponry have been recovered, including swords, daggers, spears, lances, battle-axes, scimitars, shields, crossbows, and crossbow triggers. About of the recovered items are arrowheads, which are usually found in bundles of 100 units.[28] [49] [fifty] Studies of these arrowheads suggests that they were produced by self-sufficient, autonomous workshops using a procedure referred to every bit cellular product or Toyotism.[51] Some weapons were coated with a 10–fifteen micrometer layer of chromium dioxide earlier burying that was believed to have protected them from any form of decay for the last 2200 years.[52] [53] However, research in 2019 indicated that the chromium was merely contamination from nearby lacquer, not a means of protecting the weapons. The slightly alkaline pH and small particle size of the burial soil most likely preserved the weapons.[54]

The swords comprise an blend of copper, tin, and other elements including nickel, magnesium, and cobalt.[55] Some carry inscriptions that engagement their manufacture to between 245 and 228 BCE, indicating that they were used before burial.[56]

Scientific enquiry

In 2007, scientists at Stanford University and the Advanced Light Source facility in Berkeley, California, reported that powder diffraction experiments combined with free energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and micro-X-ray fluorescence analysis showed that the process of producing terracotta figures colored with Chinese regal dye consisting of barium copper silicate was derived from the knowledge gained by Taoist alchemists in their attempts to synthesize jade ornaments.[57] [58]

Since 2006, an international team of researchers at the UCL Institute of Archaeology take been using analytical chemistry techniques to uncover more details about the production techniques employed in the creation of the Terracotta Ground forces. Using X-ray fluorescence spectrometry of forty,000 bronze arrowheads arranged in groups of 100, the researchers reported that the arrowheads within a unmarried package formed a relatively tight cluster that was different from other bundles. In addition, the presence or absenteeism of metallic impurities was consistent within bundles. Based on the arrows' chemic compositions, the researchers concluded that a cellular manufacturing organisation like to the one used in a modern Toyota factory, every bit opposed to a continuous assembly line in the early days of the automobile manufacture, was employed.[59] [60]

Grinding and polishing marks visible under a scanning electron microscope provide evidence for the earliest industrial use of lathes for polishing.[59]

Exhibitions

The offset exhibition of the figures outside of China was held at National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne in 1982.[61]

A drove of 120 objects from the mausoleum and 12 terracotta warriors were displayed at the British Museum in London as its special exhibition "The Start Emperor: Red china's Terra cotta Regular army" from 13 September 2007 to Apr 2008.[62] This exhibition made 2008 the British Museum'southward most successful year and fabricated the British Museum the Great britain's acme cultural allure between 2007 and 2008.[63] [64] The exhibition brought the virtually visitors to the museum since the King Tutankhamun exhibition in 1972.[63] It was reported that the 400,000 advance tickets sold out and so fast that the museum extended its opening hours until midnight.[65] Co-ordinate to The Times, many people had to be turned away, despite the extended hours.[66] During the mean solar day of events to marker the Chinese New year, the crush was then intense that the gates to the museum had to be shut.[66] The Terra cotta Army has been described as the only other set of historic artifacts (forth with the remnants of wreck of the RMS Titanic) that can depict a oversupply by the name alone.[65]

Warriors and other artifacts were exhibited to the public at the Forum de Barcelona in Barcelona betwixt 9 May and 26 September 2004. It was their most successful exhibition ever.[67] The aforementioned exhibition was presented at the Fundación Canal de Isabel Ii in Madrid betwixt October 2004 and January 2005, their most successful ever.[68] From December 2009 to May 2010, the exhibition was shown in the Centro Cultural La Moneda in Santiago de Chile.[69]

The exhibition traveled to Due north America and visited museums such as the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, California, Houston Museum of Natural Science, High Museum of Art in Atlanta,[70] National Geographic Order Museum in Washington, D.C. and the Regal Ontario Museum in Toronto.[71] Subsequently, the exhibition traveled to Sweden and was hosted in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities betwixt 28 August 2010 and 20 Jan 2011.[72] [73] An exhibition entitled 'The Kickoff Emperor – China's Entombed Warriors', presenting 120 artifacts was hosted at the Fine art Gallery of New S Wales, between 2 December 2010 and 13 March 2011.[74] An exhibition entitled "L'Empereur guerrier de Chine et son armée de terre cuite" ("The Warrior-Emperor of China and his terra cotta army"), featuring artifacts including statues from the mausoleum, was hosted by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from 11 Feb 2011 to 26 June 2011.[75] In Italian republic, from July 2008 to sixteen November 2008, five of the warriors of the terracotta army were displayed in Turin at the Museum of Antiquities,[76] and from 16 April 2010 to 5 September 2010 were exposed 9 warriors in Milan, at the Royal Palace, at the exhibition entitled "The Two Empires".[77] The group consisted of a horse, a advisor, an archer and six lancers. The "Treasures of Ancient People's republic of china" exhibition, showcasing 2 terracotta soldiers and other artifacts, including the Longmen Grottoes Buddhist statues, was held between 19 February 2011 and 7 November 2011 in four locations in India: National Museum of New Delhi, Prince of Wales Museum in Mumbai, Salar Jung Museum in Hyderabad and National Library of India in Kolkata.[ citation needed ]

Soldiers and related items were on brandish from 15 March 2013 to 17 November 2013, at the Historical Museum of Bern.[78]

Several Terracotta Regular army figures were on display, forth with many other objects, in an exhibit entitled "Historic period of Empires: Chinese Fine art of the Qin and Han Dynasties" at The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art in New York City from 3 April 2017, to 16 July 2017.[79] [fourscore] An exhibition featuring 10 Terracotta Army figures and other artifacts, "Terracotta Warriors of the Kickoff Emperor," was on display at the Pacific Science Center in Seattle, Washington, from eight April 2017 to iv September 2017[81] [82] before traveling to The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to be exhibited from xxx September 2017 to 4 March 2018 with the addition of augmented reality.[83] [84]

An exhibition entitled "China's First Emperor and the Terracotta Warriors" was at the Earth Museum in Liverpool from 9 February 2018 to 28 October 2018.[85] This was the start fourth dimension in more than 10 years that the warriors travelled to the Britain.

An exhibition bout of 120 real-size replicas of Terracotta statues was displayed in the German cities of Frankfurt am Main, Munich, Oberhof, Berlin (at the Palace of the Republic) and Nuremberg betwixt 2003 and 2004.[86] [87]

Gallery

See also

- List of Globe Heritage Sites in China

- Qin bronze chariot

Notes

- ^ Lu Yanchou; Zhang Jingzhao; Xie Jun; Wang Xueli (1988). "TL dating of pottery sherds and broiled soil from the Xian Terracotta Army Site, Shaanxi Province, China". International Journal of Radiation Applications and Instrumentation D. 14 (1–2): 283–286. doi:10.1016/1359-0189(88)90077-5.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 167.

- ^ a b "Decoding the Mausoleum of Emperor Qin Shihuang". Cathay Daily. thirteen May 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 6 《史記•秦始皇本紀》 Original text: 始皇初即位,穿治酈山,及並天下,天下徒送詣七十餘萬人,穿三泉,下銅而致槨,宮觀百官奇器珍怪徙臧滿之。令匠作機駑矢,有所穿近者輒射之。以水銀為百川江河大海,機相灌輸,上具天文,下具地理。以人魚膏為燭,度不滅者久之。二世曰:"先帝後宮非有子者,出焉不宜。" 皆令從死,死者甚眾。葬既已下,或言工匠為機,臧皆知之,臧重即泄。大事畢,已臧,閉中羨,下外羨門,盡閉工匠臧者,無複出者。樹草木以象山。 Translation: When the First Emperor ascended the throne, the digging and preparation at Mount Li began. Afterward he unified his empire, 700,000 men were sent there from all over his empire. They dug down deep to secret springs, pouring copper to identify the outer casing of the coffin. Palaces and viewing towers housing a hundred officials were built and filled with treasures and rare artifacts. Workmen were instructed to make automatic crossbows primed to shoot at intruders. Mercury was used to simulate the hundred rivers, the Yangtze and Xanthous River, and the great ocean, and gear up to flow mechanically. Above, the sky is depicted, below, the geographical features of the land. Candles were made of "mermaid"'due south fatty which is calculated to burn and not extinguish for a long time. The Second Emperor said: "Information technology is inappropriate for the wives of the late emperor who take no sons to be gratis", ordered that they should accompany the expressionless, and a great many died. After the burial, information technology was suggested that it would be a serious breach if the craftsmen who constructed the tomb and knew of its treasure were to divulge those secrets. Therefore, after the funeral ceremonies had completed, the inner passages and doorways were blocked, and the exit sealed, immediately trapping the workers and craftsmen inside. None could escape. Trees and vegetation were and so planted on the tomb mound such that information technology resembled a hill.

- ^ "Chinese terra cotta warriors had real, and very carefully fabricated weapons". The Washington Mail service. 26 November 2012.

- ^ Clements 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Shui Jing Zhu Chapter 19 《水經注•渭水》Original text: 秦始皇大興厚葬,營建塚壙於驪戎之山,一名藍田,其陰多金,其陽多美玉,始皇貪其美名,因而葬焉。

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 202.

- ^ Shui Jing Zhu Affiliate 19 《水經注•渭水》 Original text: 項羽入關,發之,以三十萬人,三十日運物不能窮。關東盜賊,銷槨取銅。牧人尋羊,燒之,火延九十日,不能滅。Translation: Xiang Yu entered the gate, sent forth 300,000 men, just they could not terminate conveying away his loot in 30 days. Thieves from northeast melted the coffin and took its copper. A shepherd looking for his lost sheep burned the place, the fire lasted 90 days and could non exist extinguished.

- ^ Sima Qian – Shiji Volume 8 《史記•高祖本紀》 Original text: 項羽燒秦宮室,掘始皇帝塚,私收其財物 Translation: Xiang Yu burned the Qin palaces, dug up the Starting time Emperor's tomb, and expropriated his possessions.

- ^ Han Shu《漢書·楚元王傳》:Original text: "項籍焚其宮室營宇,往者咸見發掘,其後牧兒亡羊,羊入其鑿,牧者持火照球羊,失火燒其藏槨。" Translation: Xiang burned the palaces and buildings. Later observers witnessed the excavated site. Afterward, a shepherd lost his sheep which went into the dug tunnel; the shepherd held a torch to look for his sheep, and accidentally set fire to the identify and burned the coffin.

- ^ "Purple Chinese treasure discovered". BBC News. 20 October 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Agnew, Neville (three August 2010). Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road. Getty Publications. p. 214. ISBN978-1606060131 . Retrieved eleven July 2012.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (12 April 2017). "The Army that Conquered the Earth". BBC.

- ^ O. Louis Mazzatenta. "Emperor Qin's Terracotta Army". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ^ The precise coordinates are 34°23′5.71″N 109°xvi′23.19″E / 34.3849194°North 109.2731083°E / 34.3849194; 109.2731083 )

- ^ Clements 2007, pp. 155, 157, 158, 160–161, 166.

- ^ "Archaeologist Who Uncovered China's 8,000-Man Terra cotta Army Dies At 82". npr.org.

- ^ "Army of Terracotta Warriors". Alone Planet.

- ^ "Discoveries May Rewrite History of China's Terra-Cotta Warriors". 12 Oct 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ 73号 Qin Ling Bei Lu (1 January 1970). "Google maps". Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Clements 2007, p. 160.

- ^ a b "The First Emperor". Channel4.com. Retrieved three December 2011.

- ^ "Awarding of geographical methods to explore the underground palace of the Emperor Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum". Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Nature (2003). "Terracotta Army saved from crack up". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news031124-7. Retrieved iii December 2011.

- ^ Larmer, Brook (June 2012). "Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color". National Geographic. p. 86. Print.

- ^ a b "The Necropolis of First Emperor of Qin". History.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved three Dec 2011.

- ^ Lothar Ledderose. A Magic Ground forces for the Emperor.

- ^ Ledderose 1998, pp. 51–73 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLedderose1998 (help) "A Magic Regular army for the Emperor".

- ^ "The Mausoleum of the First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty and Terracotta Warriors and Horses". Communist china.org.cn. 12 September 2003. Retrieved iii December 2011.

- ^ Portal 2007.

- ^ "China unearths 114 new Terracotta Warriors". BBC News. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Terra cotta Accessory Pits". Travelchinaguide.com. x October 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ a b The Terracotta Warriors. National Geographic Museum. p. 27.

- ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Inner Traditions Behave and Visitor. pp. 105–112. ISBN978-1591430339.

- ^ Cotterell, Maurice (June 2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Clandestine Codes of the Emperor's Army. Inner Traditions Conduct and Company. pp. 103–105. ISBN978-1591430339.

- ^ a b c Larmer, Brook (June 2012). "Terra-Cotta Warriors in Color". National Geographic. pp. 74–87.

- ^ lie, Ma (9 September 2010). "Terracotta army emerges in its true colors". Prc Daily . Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ Imperial Tombs of Red china. Lithograph Publishing Visitor. 1995. p. 76.

- ^ "Early links with West likely inspiration for Terra cotta Warriors, argues SOAS scholar". School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London.

- ^ Lukas Nickel (2013). The Start Emperor and sculpture in Cathay. SOAS, University of London: Cambridge Academy Press.

- ^ "Western contact with Mainland china began long before Marco Polo, experts say". BBC. 12 Oct 2016.

- ^ Johnston, Ian (13 October 2016). "Ancient Greeks may have built China'southward famous Terracotta Army – ane,500 years before Marco Polo". Independent.co.uk . Retrieved xiv October 2016.

- ^ a b Hanink, Johanna; Silva, Felipe Rojas (twenty November 2016). "Why Cathay's Terracotta Warriors Are Stirring Controversy". Alive Scientific discipline. Originally published in Hanink, Johanna; Silva, Felipe Rojas (18 November 2016). "Why there'southward and so much backlash to the theory that Greek art inspired China's Terracotta Army". The Conversation.

- ^ a b "Chinese archaeologist refutes BBC report on Terracotta Warriors". China Daily 中國日報. Xinhua 新華網. world wide web.chinadaily.com. 18 October 2016. Retrieved ix June 2021.

- ^ "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Upf.edu. 1 October 1979. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Portal 2007, p. 170.

- ^ "Exquisite Weaponry of Terracotta Regular army". Travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Marcos Martinón-Torres; Xiuzhen Janice Li; Andrew Bevan; Yin Xia; Zhao Kun; Thilo Rehren (2011). "Making Weapons for the Terracotta Army". Archaeology International. 13: 65–75. doi:10.5334/ai.1316.

- ^ Pinkowski, Jennifer (26 Nov 2012). "Chinese terracotta warriors had real, and very carefully made, weapons". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Terracotta Warriors (Terracotta Army)". Prc Bout Guide. Retrieved 28 July 2011.

- ^ Zhewen Luo (1993). China's imperial tombs and mausoleums. Foreign Languages Press. p. 102. ISBN978-7-119-01619-ane . Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; et al. (4 Apr 2019). "Surface chromium on Terracotta Regular army bronze weapons is neither an ancient anti-rust treatment nor the reason for their skilful preservation". Scientific Reports. ix (ane): 5289. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.5289M. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-40613-7. PMC6449376. PMID 30948737.

- ^ "Terra cotta Warriors" (PDF). National Geographic. 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2011. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ "The First Emperor – China's Terracotta Ground forces – Instructor's Resource Pack" (PDF). British Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ Bertrand, Loïc; Robinet, Laurianne; Thoury, Mathieu; Janssens, Koen; Cohen, Serge X.; Schöder, Sebastian (26 Nov 2011). "Cultural heritage and archaeology materials studied by synchrotron spectroscopy and imaging". Applied Physics A. 106 (2): 377–396. doi:10.1007/s00339-011-6686-four. S2CID 95827070. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ Liu, Z.; Mehta, A.; Tamura, Northward.; Pickard, D.; Rong, B.; Zhou, T.; Pianetta, P. (Nov 2007). "Influence of Taoism on the invention of the purple paint used on the Qin terra cotta warriors". Journal of Archaeological Science. 34 (11): 1878–1883. CiteSeerXx.1.i.381.8552. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.01.005.

- ^ a b Rees, Simon (6 March 2014). "Chemistry unearths the secrets of the Terra cotta Army". Educational activity in Chemistry. Vol. 51, no. 2. Purple Society of Chemistry. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, Marcos; Li, Xiuzhen Janice; Bevan, Andrew; Xia, Yin; Zhao, Kun; Rehren, Thilo (20 Oct 2012). "Xl Thousand Arms for a Unmarried Emperor: From Chemic Data to the Labor Organization Behind the Bronze Arrows of the Terracotta Regular army" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 21 (three): 534. doi:10.1007/s10816-012-9158-z. S2CID 163088428.

- ^ Jefferson, Dee (16 December 2018). "China's terracotta warriors volition visit Melbourne for National Gallery of Victoria'southward Winter Masterpieces serial". Arts. ABC News.

- ^ "The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army". British Museum. Archived from the original on eleven August 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b Higgins, Charlotte (2 July 2008). "Terracotta army makes British Museum favourite attraction". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "British Museum sees its most successful year e'er". All-time Western. 3 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ a b "British Museum ponders 24-hour opening for terracotta warriors". CBC News. 22 November 2007.

- ^ a b Whitworth, Damian (9 July 2008). "Is the British Museum the greatest museum on earth?". The Times. London. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ DesarrolloWeb (nineteen Apr 2007). "Los guerreros de Xian, en el Forum de Barcelona". Guiarte.com. Retrieved three December 2011.

- ^ "Guerreros de Xian". Futuropasado.com. Archived from the original on nineteen March 2019. Retrieved iii Dec 2011.

- ^ "Llegan a Chile los legendarios Guerreros de Terracota de China". Latercera.com. Archived from the original on 21 Oct 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Record-Breaking Terracotta Regular army Exhibition at Atlanta museum". Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved sixteen January 2010.

- ^ "ROM's terracotta warriors show a blockbuster". CBC. half dozen January 2011.

- ^ "China's Terracotta Ground forces, Stockholm, Sweden, Reviews". Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ^ "Globe Famous Terracotta Ground forces Arrives in Stockholm for Exhibition at Ostasiatiska Museum". Retrieved xx January 2010.

- ^ "Terracotta warriors, Picassos heading to Sydney". ABC News. fourteen October 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Empereur Guerrier De Chine Et Son Armee De Terre Cuite". Mbam.qc.ca. Archived from the original on xxx September 2011. Retrieved iii Dec 2011.

- ^ "Il Celeste Impero. Guerrieri di terracotta a Torino – Il Sole 24 ORE".

- ^ "Esercito di Terracotta: dalla Cina a Palazzo Reale di Milano – NanoPress Viaggi".

- ^ "Die Terrakotta-Krieger sind da". Der Bund. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ Historic period of Empires: Chinese Fine art of the Qin and Han Dynasties Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ 'Historic period of Empires: Chinese Fine art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220)' Review: Treasures of Nation-Building Wall Street Journal

- ^ Upchurch, Michael (7 April 2017). "'Terracotta Warriors' exhibit makes grand entrance at Pacific Scientific discipline Heart". Seattle Times . Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Terra cotta Warriors of the Starting time Emperor". Pacific Science Center. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Why the Terracotta Warriors are so special, and how to meet them in Philly". Philly.com . Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Hurdle, Jon (29 September 2017). "Arming China's Terracotta Warriors – With Your Phone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "World Museum, Liverpool museums". www.liverpoolmuseums.org.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland . Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Einmarsch der Chinesen". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). 16 January 2004. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ "Tschüss Berlin! Terrakotta-Krieger des Kaisers von China ziehen weiter". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 25 July 2004. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

Bibliography

- Clements, Jonathan (xviii January 2007). The Outset Emperor of Mainland china. Sutton. ISBN978-0-7509-3960-seven.

- Debaine-Francfort, Corinne (1999). The Search for Ancient Cathay. 'New Horizons' series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-30095-4.

- Dillon, Michael (1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary . Durham Eastern asia serial. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN978-0-7007-0439-ii.

- Portal, Jane (2007). The Beginning Emperor: China'due south Terracotta Army. Harvard University Press. ISBN978-0-674-02697-ane.

- Ledderose, Lothar (2000). "A Magic Army for the Emperor". Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. The A.Westward. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-00957-five.

- Perkins, Dorothy (2000). Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Facts On File. ISBN978-0-8160-4374-3.

External links

- UNESCO description of the Mausoleum of the Beginning Qin Emperor

- Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum (official website)

- People's Daily article on the Terracotta Regular army

- OSGFilms Video Article : Terracotta Warriors at Discovery Times Square

- Tomb of the First Emperor of China by Professor Anthony Barbieri, UCSB

- China's Terracotta Warriors Documentary produced by the PBS Series Secrets of the Dead

stallingstheethem.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terracotta_Army

0 Response to "Which Method of Creating Art Was Used to Produce Over 6000 Life Sized Ceramic Warriors and Horses?"

Enviar um comentário